I have struggled to write blog posts in Turkish for the last few weeks. Although the most obvious reason is that I have not lived in Turkey for the previous 2.5 years, I don’t believe this is the case. I think not reading enough Turkish literature caused the more-than-necessary stalls while writing. So, to improve my language usage and to broaden my perspective, I bought 15 Turkish books on self-development and psychology, written mainly by respected Turkish scientists in the field.

Among those 15 books, I would like to discuss the first book I recently finished: 10 Experiments to Change Your Perspective: Human by Prof. Selcuk Sirin. Unfortunately, it’s not translated into English. Anyways, in addition to authoring several books on the intersection of psychology, sociology, and politics, he is one of the most cited applied psychology researchers in developmental psychology, working at New York University. He is known to spread scientific knowledge in the area of developmental psychology to both local and global communities.

Today, I’d like to mention three of the ten experiments he talks about in his book. These experiments are the backbones of modern psychology research, as almost all psychology students know them by heart. Then, I’ll point out two overlaps in the experiments to emphasize the importance of our (digital) surroundings in this day and age.

Before briefly discussing the experiments, here is their first overlap: they originated from scientific curiosity after World War II. Especially after the Nazi regime, these scientists wanted to answer a simple question: Whether conformity and evil acts come from nature or nurture? They wondered how a human being could be capable of such cruel acts. To answer this, they set up experiments that would eventually become the foundations of psychological research and it’s ethics. Let’s get to it.

1- Asch’s Conformity Experiment (1951)

Look at the lines below. Which line on the right is the same length as the left? It’s quite easy to answer, right?

In this experiment (which originated from another Turkish OG psychologist called Muzafer Sherif in the 1930s), Asch’s research team asked the same question to the group of participants. Here is the hack: only one in the group was actually a participant, while others acted like participants (as they were called confederates).

Many experiments and their replications in different cultural contexts produced the same results: When more than three confederates persisted in the wrong answer, the actual participant in the group just conformed to the group and gave the wrong answer. This was the case for almost two-thirds of the actual participants.

2- Milgram’s Experiment on Obedience (1961)

How did the Nazi soldiers torture and murder millions of Jews? Did all of them have intrinsic evil inside of them, or were they obeying their authority? Milgram went on a mission to answer this question with his historical experiment on conformity.

In this experiment, participants sat down in front of an electroshock machine, mice, and a speaker. The shock machine was connected to another person in another room, which the participants could not see inside. They could only communicate with this other person via the mice and speaker in front of them. Then, participants were instructed by someone authoritative to ask the other person some questions. Whenever that person gave the wrong answer, they were instructed to provide a small electroshock. With each incorrect answer, the authoritative experimenter instructed the participants to increase the level of shock. By the way, these participants also heard the person’s screams while shocked.

The results? Almost two-thirds of the participants eventually gave the lethal dose to kill the other person. Even when they expressed their concerns, the authoritative figure said things like “Please continue the experiment” or “The experiment requires you to continue.” Note that all the participants could leave the experiment at any given moment, although the majority of them just obeyed the dude with the confident and deep voice of Blade, the vampire hunter. Luckily, the person on the other side of the room was just an actor.

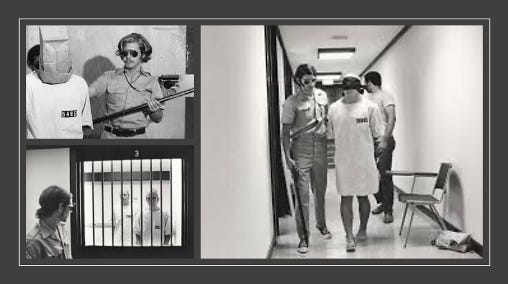

You can see the experimental setup on the left side of the images below. On the right, you can see the regret of a participant who thought he just murdered another human being just because a random authority figure instructed so:

3- Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment (1971)

In this experiment, voluntary students from Stanford University were randomly assigned to two roles: guardian and prisoner. Then, these students were invited to the basement of the psychology department at the university to play their roles in an immersive prison-like experimental setup.

What happened next was so cruel that it shaped the ethics of future experiments in psychology. The “guardian” students were so immersed in their roles that they abused the prisoners psychologically and physically. They were blindfolding prisoners and making them do pushups or manhandling them when they disobeyed. Then, the students who had the prisoner role were psychologically crushed, showing symptoms of depression and withdrawal, just like prisoners in real life. Sometimes, a couple of prisoner students questioned the justice of their treatment, resulting in more punishment, not only by guardians but also by fellow prisoners! In this case, prisoners were gossiping about how bad of a prisoner he was by questioning the authority.

Meanwhile, Zimbardo also played a role. He was the superintendent of the guardians in his experiment. He was so absorbed in this “experience” that he couldn’t realize the problem in plain sight. Then, along with his future wife and a minority of the students in the experiment, he was convinced to stop the two-week experiment on the sixth day. One student left the experiment early because he had a nervous breakdown. Multiple students ended up needing psychological help after the experiment as they were traumatized. Here are some of the actual pictures from the experiment:

So, do evil and obedience come from nature or nurture?

As I mentioned earlier, let’s get back to the first commonality between these experiments. Do people conform social norms, injustice, and cruelty because of their nature (i.e., their genetics) or environment? It’s a hot debate in psychology for many decades now. Although the question requires a deeply nuanced answer, I’ll give you the short version of it, especially in the context of evil: At the beginning of life, genetics is essential, but over time, nurture becomes more prominent. Plus, the environment we grow up in can change our genetics, and our genetics can determine our environment (as may it sound impossible). Even though some people are born with genetics that predisposing them to violent acts, a good family and growing environment can neutralize the genetic effects. I recommend Adrian Raine’s book on this for the more sophisticated answer: Anatomy of Violence.

So, even if our nature is an important factor in our behavior, should it be the end of the story? I don’t think so. I think nature is not in our control as nobody chooses where they were born. We can only have an impact on things we can control, regardless of how limited that control might be. We saw the circumstances, even though they were randomly assigned to random people, turn students into sadistic guardians or make them obey the group when it’s the wrong thing to do. So, even if we don’t get to control our nature, we can at least try to control our environment.

Sure, but what environment?

Our lives have many environments: family, friends, workplace, and country. Changing our family or country can sometimes be challenging (or impossible). It depends on person to person and circumstance to circumstance. However, one environment is 100% in our control, and I want to focus on this environment: social media.

There are two points I want to mention regarding the role of digital environments. The first one is that social media algorithms work in our interest so intensely that we can see what we are interested in, even in cases where we don’t realize it! Then, we engage in these interesting contents, resulting in even more similar contents and more like-minded people in our feed. Eventually, this situation results in echo chambers, where people only get the reflection on their points of view. After some point, such echo chambers can create strong polarizations on many topics, including the ones that discuss which partner was the best for Selena Gomez, not even mentioning the hot topics on politics.

The second point I’d like to talk about is engagement farming. Remember the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal. The company used unauthorized customer data to win elections in different continents, not to mention their intentional influence on public opinion on Brexit! Although they left their space to digital automation, thousands of people wake up in the morning, shower, commute to work, and create fake content or comments for eight hours straight for a living. These firms exploit human psychology and use big data to present “facts” to correct people in the right way at the right time and right place.” It’s a business. I am not even mentioning the deepfakes to create realistic videos or other artificial intelligence methods that can do all these things within seconds.

The second overlap between studies: The invisible heroes

As you might have noticed, I highlighted several words while discussing the experiments. There is a statistical overlap among all these studies: their surprising effects were seen in approximately two-thirds of the participants. It means, as Sirin mentions in his book, one-third of the participants said, “Yo, I’m not buying this!”. They refused to obey. They refused to harm others just because some random dude with a deep voice instructed so. They were the brave ones, the invisible heroes of the society. This was still the case when scientists from different countries and cultures replicated these experiments.

As I was mentioning heroes, Zimbardo, from Stanford prison experiment, actually dedicated his life to a non-profit project called Heroic Imagination Project:

Today, HIP’s mission is rooted in the findings of social psychological experiments of Asch, Milgram and Zimbardo, among many other. These experiments, as well as myriad heinous acts throughout history, reveal the “banal” side of evil, as described by Hannah Arendt. No one is exempt from the possibility of being coerced by the dark side of human nature.

However, the reverse also appears true. The “banality of heroism”, an idea first explored in a 2006 article written by Dr. Zimbardo and Dr. Zeno Franco, is a guide for HIP’s work, suggesting that each and every seemingly ordinary person on this planet is capable of committing heroic acts.

From this core belief, the Heroic Imagination Project was born with a mission to use important findings in psychology to equip ordinary people of all ages with the knowledge, skills, and strategies necessary to choose wise and effective acts of heroism during challenging moments in their lives.

Like Zimbardo, it gives me hope that no matter the circumstances, there is always a group of people who can say NO. No to injustice. No to cruelty. No to conformity.

Of course, one might object that the concept of evil, conformity, or justice can change people to people, society to society, and circumstances to circumstances. As I mentioned in “To Think, or Not to Think. Like Socrates”, we all need to think critically and tailor concepts like justice or good to our unique lives. We need to step outside of our predetermined beliefs of our parents, teachers, friends, or communities. More importantly, we need to have the courage to question our assumptions.

To start diving into this rabbit hole of belief systems, we can begin by focusing on what we can control and develop endurance for what we can’t control. Although our nature (i.e., our genetics) significantly impacts our lives, we can’t control it. What we can control is our environment, regardless of how limited it might be. I can’t speak on behalf of people in hard-to-leave environments, so today, I wanted to focus on the digital environment we are surrounded with. That is something we can control.

Perhaps we are swimming in a sea of ideas, heads submerged in the water. We may need to lift our heads above the water and see where we are. Perhaps we are on the wrong side of the shore. Perhaps we are on the wrong side of cruelty, justice, and conformity. Perhaps all those echo chambers are designed to keep our heads submerged as much as possible. OR, perhaps we will see that we are on the right track, but we need to get some air and see fresh perspectives. In this day and age, the content we consume is as essential as the food we consume. Let’s remember that.

Best regards,

Bugra