A warning against the psychological warfare in the attention economy.

Recently, I read “How to Think Like Socrates” by Donald Robertson, a cognitive behavioral therapist and author of high-quality books on Stoicism. In this book, he connects the Socratic way of thinking with modern psychology while trying to give a semi-fictional historical account of Socrates and the city of Athens.

Today, I would like to discuss Robertson’s book first, then combine his ideas with modern economic psychology research to point out a vital societal problem: not thinking like Socrates. I’m not claiming that everybody should think about philosophy in their free time, but everybody needs to have the ability to question, like Socrates, so as not to consume all the nonsense all the time.

Socrates: the ruthless warrior

I assume many of you know Socrates as the short and bald guy who nagged people with his questions, leading to his execution. Yes, that is true, but he was also a foot soldier, in fact, one of the greatest ones. He showed exceptional courage and endurance during the three wars he attended. He was known to deter the enemies on the battlefield because of the way he fought. Those enemy dudes avoided his wrath and tried to find others to attack. Consequently, he saved many lives, which led to a medal of honor at one point, but he refused. He preferred it be given to his mentee, Alcibiades, who was noble, bright, attractive, and had a shining political career that could help the Athenians.

Independent of Alcibiades and the Medal of Honor, Socrates was also known for his distance from the public stage. Contrary to him, at the time, Sophists were paid quite heavily to teach their wisdom in different forms, such as philosophy, politics, and rhetoric—the art of persuasive speaking. They were like today’s self-help gurus.

Among those teachable assets, rhetoric was in demand, like a best-selling Udemy course on AI. It’s because Athenians were governed by the ecclesia, the Assembly, a group of citizens who made the big decisions. This assembly formed the Athenian democracy, which was open to all male adult citizens, the closest thing to democracy at the time. Periodically, these citizens would gather on a large hill and vote for governmental decisions. Then, as you can imagine, the ability to persuade crowds was perhaps the only skill one needed to have absolute power. So, most wealthy people hired these Sophists to teach them or their offspring about persuasion and public speaking.

Getting back to Socrates, he didn’t like these Sophists because they weren’t focusing on what they conveyed with their mouths. It didn’t matter to them whether what they were saying was true or not, right or wrong, just or unjust. They were talking about what others wanted to hear or what would capture their attention. Socrates called this pandering, which is what most modern-day influencers also practice. In this day and age, with all those smooth talkers on social media, when you are pandered, you consume the ideas or beliefs of others without thinking about them. You acquire them passively, as Robertson put it in his book. It prohibits you from thinking for yourself. He says that you get opinions, which are “the appearance of knowledge rather than genuine knowledge.”

Coming back to modern-day psychology: System 1 & 2

This pandering phenomenon is also present in the literature on psychology, particularly economic and consumer psychology. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize winner for economics, shows that there are always two systems in your mind. System 1 is your mind’s fast and automatic mode that handles instant reactions, intuitions, or danger sensing. It works so fast that it is almost impossible to control, so it is highly prone to manipulation. On the other hand, system 2 is the slow and effortful brain mode. You use it for actual thinking, like solving a math problem or your co-worker’s bizarre behavior for the last two weeks.

I believe that a significant portion of modern-day Sophists — the self-help or god-knows-what gurus on social media— use psychological methods to influence your System 1, which is more prone to manipulation than System 2. When these influencers speak smoothly and have some good points during their speech (or writing), you don’t spend time thinking it through. With the “tiktokification” of social media, almost all social media applications now have short-form content, making it harder for you to stop. These social media companies know the human psyche from the inside out, so it is no wonder there is a continuing debate about whether this compulsive usage should be treated as a mental disorder or the new normal.

Let’s return to pandering and acquire information passively. During the doom scrolling, how often do you stop and reflect on that excellent insight on detecting energy vampires in your lives? Or the narcissists? If you actually stop, think, and do your research (which is what you use System 2 for), you would see that only around 0- 6% of the population has narcissistic personality disorder. It is a rare disorder. It’s really rare. BUT, as Kahneman showed, you don’t get to control your system 1, so when you see a convincing argument on Instagram, you feel that inner joy of becoming a psychologist and of diagnosing your partner with narcissism because they forgot to wash the dishes yesterday.

The dark side of the moon: WYSIATI

There is a cool name with a cool abbreviation for this blindness: what you see is all there is (WYSIATI). It is a great title for a magician-criminals type of movie. Anyways, ChatGPT did a better job than me in explaining this phenomenon:

Our brain jumps to conclusions based on the information we have right now without considering what we don’t know. In other words, we believe the story in front of us, even if it’s incomplete.

When you see that convincing post on the morning routine of the greatest businessman of all time, you don’t think there is more to it. You don’t think it’s extremely rare to succeed at the top level at anything, for that matter. You miss the fact that there are many conditions, other than pure willpower, ambition, and hard work, to accomplish on the highest levels. But that efficient morning routine on Instagram seems convincing; more importantly, it is relatable. Or when you see someone slipping two times in a row out of nowhere, all you see is all there is: the dude is clumsy. Perhaps he just ate a Big Mac menu even though he has a blood pressure problem and got dizzy, or he has a neurodegenerative disorder in his brain, causing him to lose balance.

Our brain excels at filling in the blanks. It doesn’t want to put too much effort and spend its valuable resources on every little thing happening around us. It only wants to put that cognitive effort when it’s actually needed, but even that’s rare (I was going to say, “Imagine that homework you didn’t want to do in high school,” but I think you can find many examples from last week alone). The smooth-talking is not the end of the story, by the way. I want to list three of the most popular logical fallacies or biases that can be used against you to manipulate your opinions or sell you that course on how to make money fast:

Anecdotal Fallacy: Using personal experiences without a statistically significant number of cases. The more vivid the anecdote, the more likely people are to believe it. Imagine that smooth-talker uncle who tells stories so well that you unconsciously nod your head. The story is given to you so clearly that it is almost impossible to think of any other explanations since all you see is all there is, and there is nothing more to it.

Appeal to Ignorance is assuming a claim to be true because it has not been proven false or cannot be proven false. An excellent example regarding recent history would be claiming that new vaccines have no adverse side effects because nobody has shown them so far. If all you see is all there is, it means that when you don’t see anything at all, you conclude that nothing exists.

Halo Effect: When you like someone in one aspect, it spreads to other aspects. It’s a known fact that judges sentence attractive people with less punishment compared to their not-so-attractive criminal peers. Similarly, if you don’t like someone in one aspect, you tend not to appreciate other aspects even though they are worthy of your appreciation. This holds for brands, people, and everything you can think of.

How can you shield against it?

For Robertson, and therefore Socrates in this case, real wisdom requires knowing how to navigate your path through life by learning to ask other people AND yourself the right questions. This questioning is not like a thing you learn once and apply for the rest of your life; it requires practice. Here are the three tips that could help:

1- Be Aware

First, be aware of the three biases mentioned earlier. Although System 1 is primarily resistant to your conscious efforts (because it works faster than conscious awareness), being aware of it can occasionally give you a heads-up, which is better than being ignorant of your faults.

2- Practice Critical Thinking

Second, take a look at my previous post about how to practice critical thinking. In this attention economy, thinking has become a lost form of art. In that post, I shared three easy-to-follow exercises for practicing clinical thinking.

3- The Two-column Exercise

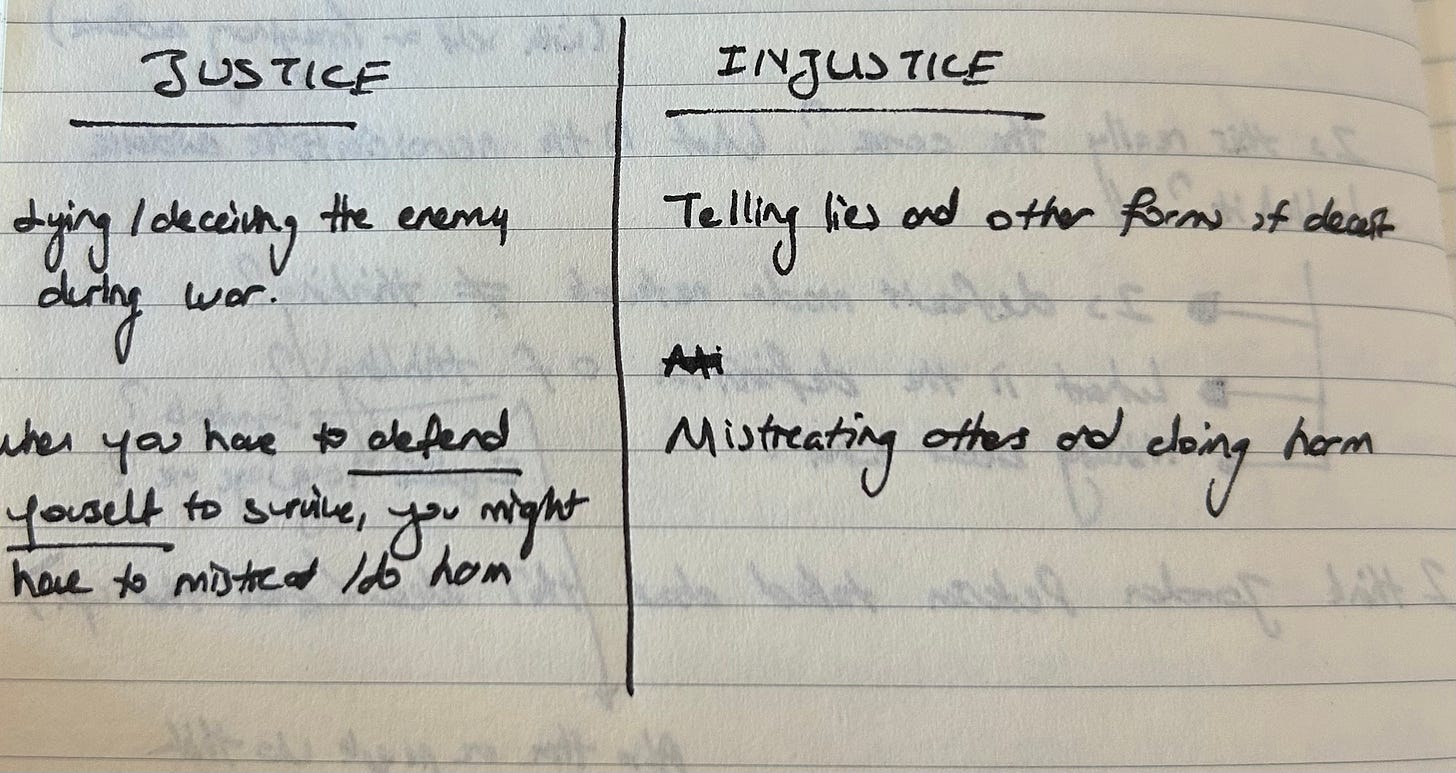

Third, think like Socrates. He was known for being a devil’s advocate and deliberately tried to find counterarguments in all the conversations. Perhaps his social intelligence was not his strong suit, but his annoying method worked like a charm. He also believed that what is right/wrong/just/unjust/good/bad depends on person to person and situation to situation. To examine any given idea or concept, such as justice, and to tailor it to a person’s unique life, Socrates had a method called the two-column exercise, which is used in modern-day cognitive therapies.

This exercise can be used for many things in cognitive behavioral therapy, including thoughts that disturb you or the cost-benefit analysis of your decisions. Since I am not an expert on cognitive behavioral therapy, I will only give an example of critical thinking using Socrates’s dialogue with his friend.

Take a piece of paper and divide it into two columns. Let’s say you want to think about justice. Ask yourself: “What is justice?” It will probably be harder to think about what it is. As Socrates discovered, people can come up with negative examples far more quickly. So, ask again: “What would be injustice?”. List all the answers in the right column. Then, on the left column, try to play devil’s advocate and find counterarguments against it. Here is an example from Donaldson’s book:

A person’s worth is measured by the worth of those he values, according to the philosopher King Marcus Aurelius. But how can you know what you actually value? How do you determine who you should be friends and partners with? Do you value being good? Then, you must know what being good looks like. Do you value being trustworthy? Then, you must know where exactly you draw the line for (white) lies. What about justice? In your relationships with others, which principles do you abide by to be just to others? Or be just to yourself? How often do you think about these primary values, even though they are lowkey dictating your life? Even if there is no space in your lives to question these primary things, what about the non-sense flood of random information you absorb daily? What would they add up to in the end, considering the limited time you have on this beautiful earth?

Best regards,

Bugra